+ Jack the Ripper

This article is about the serial killer. For other uses, see Jack the Ripper. For the murders in or near Whitechapel between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891, see Whitechapel murders.

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums of the East End of London. Their throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations. The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to speculation that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and numerous letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard from individuals purporting to be the murderer.

The name "Jack the Ripper" originated in the "Dear Boss letter" written by an individual claiming to be the murderer, which was disseminated in the press. The letter is widely believed to have been a hoax and may have been written by journalists to heighten interest in the story and increase their newspapers' circulation. The "From Hell letter" received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee came with half of a preserved human kidney, purportedly taken from one of the victims. The public came increasingly to believe in the existence of a single serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, mainly because of both the extraordinarily brutal nature of the murders and media coverage of the crimes.

Extensive newspaper coverage bestowed widespread and enduring international notoriety on the Ripper, and the legend solidified. A police investigation into a series of eleven brutal murders committed in Whitechapel and Spitalfields between 1888 and 1891 was unable to connect all the killings conclusively to the murders of 1888. Five victims—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—are known as the "canonical five" and their murders between 31 August and 9 November 1888 are often considered the most likely to be linked. The murders were never solved, and the legends surrounding these crimes became a combination of historical research, folklore, and pseudohistory, capturing public imagination to the present day.

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron

Jack the Ripper | |

|---|---|

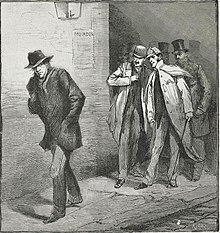

"With the Vigilance Committee in the East End: A Suspicious Character" from The Illustrated London News, 13 October 1888 | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Other names |

|

| Motive | Unknown (possibly sexual sadism and/or rage) |

| Details | |

| Victims | Unknown (5 canonical) |

| Date | 1888–1891 (1888: 5 canonical) |

| Location(s) | Whitechapel and Spitalfields, London, England (5 canonical) |

One of the first problems you encounter when you attempt to write a history of the Jack the Ripper crimes is establishing just how many of the Whitechapel Murders were, in fact, carried out by the killer who became known as Jack the Ripper.

Although the exact number of victims most frequently bandied around is five, it should be remembered that this is based upon a later statement made in 1894 by Melville Macnaghten and this is not, by any means, a definitive number.

Indeed, the Whitechapel Murders file, which is the generic file that encompasses the actual Jack the Ripper crimes has the names of eleven victims on it, some of whom were victims of Jack the Ripper, some of whom may have been, and several of whom most certainly weren't.

THE CANONICAL FIVE VICTIMS

The five aforementioned names most often put forward - and often referred to as the canonical five victims - as having been murdered by the ripper are:-

Mary Nichols - Murdered on 31st August 1888

Annie Chapman - Murdered on 8th September 1888

Elizabeth Stride - Murdered on 30th September 1888

Catherine Eddowes - Murdered on 30th September 1888

Mary Kelly - Murdered on 9th November 1888

However, the file also contains the names of two victims who were murdered before Mary Nichols, whose body was found on August 31st 1888.

The first of these victims was Emma Smith, who was attacked in the early hours of the 3rd April 1888.

She later died of her injuries in the London Hospital and, as a result, hers became the first name to appear on the Whitechapel Murders file.

Emma Smith was, almost certainly, not a victim of Jack the Ripper. Indeed, before she died, she was able to tell the doctor who treated her at the London Hospital that she had been attacked by a local gang.

MARTHA TABRAM - JACK THE RIPPER'S FIRST VICTIM?

A few months later, on the 7th August 1888, the body of Martha Tabram was found in George Yard, a sordid thoroughfare that led, and for that matter still leads, off Whitechapel High Street. She had been subjected to an horrendous and very violent attack in the course of which she had suffered 39 frenzied stab wounds to her throat, chest and abdomen

Martha Tabram (also referred to as Martha Turner) may, or may not, have been a victim of the criminal who later became known as Jack the Ripper.

The case against her having being a victim is that her throat hadn't been cut and she had not been disembowelled, injuries that almost all the canonical five victims would later endure.

Evidence that suggests she was a victim is that her killer had targeted her throat and abdomen, just as Jack the ripper would do with the five canonical victims.

It is, therefore, safe to say that the jury is, most certainly, still out on whether or not Martha was a ripper victim.

INSPECTOR ABBERLINE TAKES CHARGE

As a result, it was decided that the investigation needed to be headed by an officer who had a good working knowledge of the East End criminal underworld.

Thus it was that, in early September 1888, Inspector Frederick George Abberline - a man who, prior to his promotion out of the area the previous year, had spent the best part of fourteen years as a detective in the district where the crimes were occurring - was brought in to take overall charge of the on the ground investigation.

Abberline would become one of the most important of the investigating officers and, on the whole, he was able to avoid the general press criticism and ridicule that other, more senior officers, were subjected to.

Indeed, it seems that Abberline was universally respected, not just by his fellow police officers and superiors, but also by the press and the public at large.

THE LEATHER APRON SCARE

It was around this time that police enquiries amongst the prostitutes in the area yielded a possible suspect in the form of a man whom the local street walkers had nicknamed "Leather Apron", on account of the fact that he habitually wore such a garment.

According to the prostitutes this "Leather Apron" was running an extortion racket amongst them and threatening to rip them open if they didn't give him their money.

Unfortunately, when the press learnt of this suspect, several newspapers began emphasising the man's supposed Hebrew appearance, a fact which led to anti-Semitism surfacing in the area.

ANNIE CHAPMAN IS MURDERED

It was against this background that, on the 8th September 1888, the body of another prostitute was discovered in the back yard on 29 Hanbury Street, less than a mile away from Buck's Row where the previous murder of Mary Nichols had taken place just a week before.

The Hanbury Street victim was identified as Annie Chapman, and this time the violence had escalated, with the killer having removed and gone off with her womb.

The fact that a freshly washed leather apron was found close to her body, coupled with the press sensationalism concerning the identity and race of the polices main suspect, caused the anti-Semitism to boil over into full scale racial unrest.

Desperate to restore order, the authorities flooded the area with police officers, an action which had the effect of both stilling the agitation and, since no murders took place for a few weeks, appears to have made it difficult for the killer to strike again.

LEATHER APRON ARRESTED

Shortly after the murder of Annie Chapman, Sergeant William Thicke arrested local man John Pizer, maintaining that he was known in the area as "Leather Apron".

Pizer, however, was able to provide cast-iron alibis as to his whereabouts at the time of the most recent murders.

He was, therefore, ruled out as a suspect, and he even appeared at the inquest into Annie Chapman's death, where he was officially and publicly cleared of any involvement in the crimes.

THE MILE END VIGILANCE COMMITTEE

On the 10th September 1888, a group of local businessmen and tradesman formed the Mile End Vigilance Committee and elected local builder Mr George Lusk as their president.

In films about the Jack the Ripper murders these committees (there were several in addition to this one) are often depicted as vigilantes.

But in reality, their stated aim was to supplement the police numbers in the area and to raise sufficient funds to offer a reward for information that might lead to the killer's arrest.

As a result of his Vigilance Committee activities Mr George Lusk became something of a local celebrity and his name began appearing in the newspapers on a regular basis.

WAS THE KILLER A MEDICAL MAN?

Meanwhile, at Annie Chapman's inquest, the Divisional Police Surgeon, Dr George Bagster Philips, expressed his opinion that Annie Chapman had been murdered in order that her killer could obtain her womb. Philips also opined that the skill and speed that he displayed in removing the organ suggested that the murderer possessed some anatomical knowledge.

THE CORONER CAUSES A SENSATION

During his summing up at the inquest into Annie Chapman's death, the Coroner, Wynne Baxter, caused a sensation by revealing that the sub-curator of a Pathological Museum at one of the London Medical Schools had approached him with information about a certain American Doctor who had offered him £20 for each womb that he could provide him with.

Baxter wondered if the "knowledge of this demand" had incited some deranged wretch to carry out the most recent murder in order to obtain a womb which could, presumably, then be sold on for profit?

Needless to say Baxter's revelations and ponderings caused an absolute sensation and, it must be said, added a bizarre twist to what was rapidly becoming the pantomime of the Whitechapel Murders.

The medical profession itself, it should be said, were quick to disprove Baxter's allegations, and it is interesting to note that such a theory was not mentioned at any of the inquests into the deaths of subsequent victims.

AN INCREASED POLICE PRESENCE DETERS THE KILLER

On the streets of Whitechapel the police were battling to bring the killer (or killers) to justice and were coming in for an awful lot of press criticism for their inability to do so.

However, their increased presence appears to have deterred the killer and, by the end of September, the people of the area had begun to relax, with many of them believing that the murder spree had ended.

THE NIGHT OF THE DOUBLE MURDER

But, on 30th September 1888, the Whitechapel Murderer returned and killed two women in less than an hour.

The first victim was Elizabeth Stride, whose body was found by Louis Diemschutz, as he turned his pony an cart into a dark yard off Berner Street at 1am.

The fact that her throat had been cut, but the rest of her body had not been mutilated, led the police to surmise that the killer had, in fact, been interrupted by Diemschutz as he entered the yard.

The second victim that morning was Catherine Eddowes, whose horrifically mutilated corpse was found in Mitre Square, in the City of London, at 1.45am.

In addition to the injuries suffered by Mary Nichols and Annie Chapman, the killer had also mutilated Catherine Eddowes face. He had also removed and gone off with her uterus and left kidney.

JACK THE RIPPER'S ONLY CLUE

As the police pursued Jack the Ripper through the streets of the East End of London, they discovered a clue.

In a doorway in nearby Goulston Street, a police constable, Alfred Long, patrolling his beat came across a piece of Catherine Eddowes bloodstained apron in the doorway of an apartment block.

Scrawled in chalk on the wall above the apron was a message which read "The Juwes are the men that will not be blame for nothing."

This message was the source of a great debate between the Metropolitan Police, who wanted to erase it lest it lead to racial unrest in the district, and the City of London Police, who wanted to photograph it as they felt it might be an important lead in their hunt for the killer of Catherine Eddowes.

The dissent between the two forces was ended at 5.30am when Sir Charles Warren, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, arrived at the scene and order its immediate erasure.

THE KILLER IS GIVEN THE NAME JACK THE RIPPER

In the wake of what the press dubbed the "double event" the police decided to make public a letter which, a few days previous, had been sent to a London News Agency.

Written in red ink, it purported to have been written by the killer and boasted that the police "wont fix me yet". Having gloated over what he had done to his, supposed, victims and stating what he would do to his next victim, the author signed the letter "Jack the Ripper".

Once the police made the letter public, the name "Jack the Ripper" caught on immediately and helped turn a series of sordid East End murders into an international phenomenon. Indeed, it is safe to say that part of the reason why this particular set of crimes are still so famous is because of that name.

HOAX LETTERS START COMING IN

Unfortunately, releasing the letter proved to be a mistake.

The police quickly deduced that it hadn't been written by the killer but, rather, was the work of a London journalist.

However, such was the allure of the name, hoaxers began sending in letters with the same or, or similar, signatures and the police investigation came close to melt down with this veritable avalanche of Jack the Ripper correspondence.

MR LUSK'S LETTER FROM HELL

One of the most famous of these prank missives was sent to Mr George Lusk, the president of the Mile End Vigilance Committee, in mid-October 1888.

Famously, this was letter was addressed "From Hell" and it contained half a kidney which, according to the letter's writer, he "took from one victim."

Despite lurid press speculation that the kidney sent to Mr Lusk was, indeed, half of the one taken from the body of Catherine Eddowes, the consensus amongst police and doctors was that it was, in fact, a sick prank perpetrated by a medical student.

However, the whole of October went by without another murder and, once more, the people of the area entered November believing that the killing spree was over.

THE MURDER OF MARY KELLY

Their relief, however, was premature.

On the 9th November 1888 the body of Mary Kelly was found in her room at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street in Spitalfields.

Her body had been virtually skinned down to the bone. Indeed so extensive and horrific were her mutilations that her live in lover, Joseph Barnett, was only able to identify her by her eyes and ears.

Although it is generally believed that Mary Kelly was the last of Jack the Ripper's victims, there are several more names of later murder victims on the Whitechapel Murders file.

ROSE MYLETT MURDER

On 20th December 1888, Rose Mylett was found dead, but un-mutilated, in Clarke's Yard, Poplar. Although the newspapers were full of speculation that she had been murdered by Jack the Ripper, the police doctors concluded that her death had been accidental. However, the Coroner and the jury at her subsequent inquest disagreed and a verdict of "Murder by person or persons unknown." was returned.

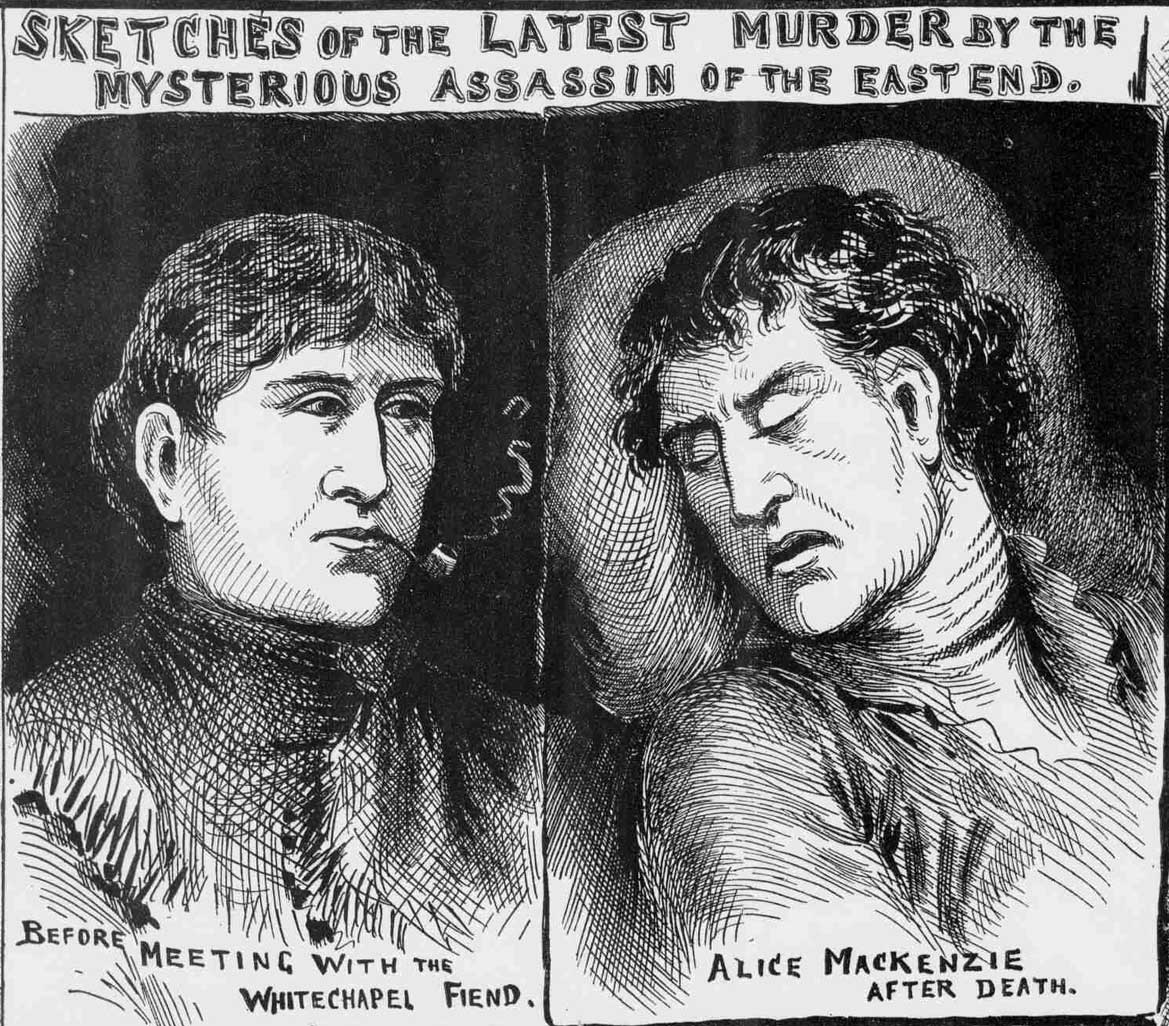

ALICE MCKENZIE'S MURDER - THE RETURN OF THE RIPPER?

On July 17th 1889 the body of Alice McKenzie was found in Castle Alley, off Whitechapel High Street.

There were two stab wounds to her throat and a long, though not unduly deep, wound ran from her left breast to her navel. In addition, there were also shallow wounds and scratches to her lower abdomen.

Although, at the time, some police officers and doctors believed that Jack the Ripper had returned, the general consensus was, and still is amongst experts, that she was not a victim of Jack the Ripper.

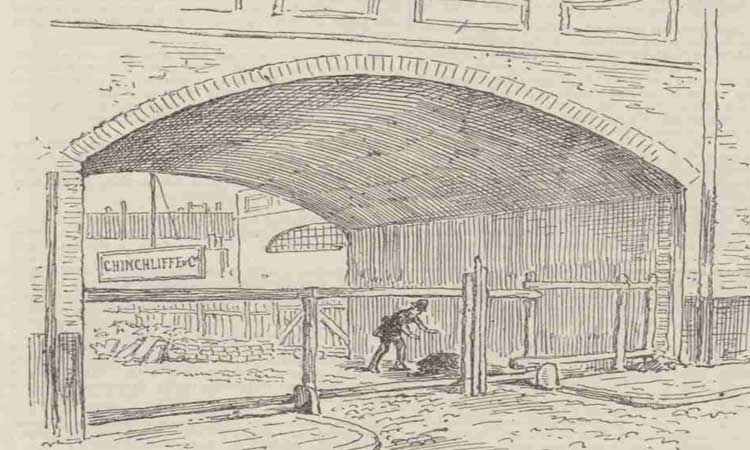

PINCHIN STREET MURDER - ANOTHER RIPPER CRIME?

On 10th September 1889 the mutilated torso of an unidentified woman was found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, a little way from Commercial Road, and a short distance from Berner Street where Elizabeth Stride had been murdered almost one year before.

Press reports at the time mentioned similarities to the mutilations to the torso and the injuries sustained by Jack the Ripper's victims, but the then Metropolitan Police Commissioner, James Monro, considered the modus operandi to be different to that of Jack the Ripper and ruled the woman out as one of his victims.

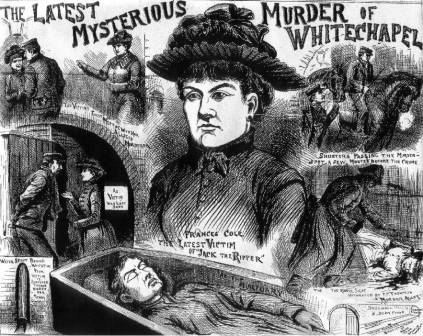

FRANCES COLES THE LAST WHITECHAPEL MURDERS VICTIM

The final name to appear on the Whitechapel Murders file is that of Frances Coles, whose body was found at 2.20am on 13th February 1891 in Swallow Gardens of Mansell Street, not far from the Tower of London.

He throat had been cut, but she had not sustained any further mutilations.

The fact that she was still alive when found, by Police Constable Ernest Thompson, led to speculation that the killer, as in the case of Elizabeth Stride, had been interrupted.

When it transpired that she had spent the days prior to her death with a sailor by the name of Thomas Sadler and that he had, not only been involved in several drunken altercations around the time of her murder, but that he had also sold a clasp knife shortly after her murder, the police arrested him and considered him a likely suspect, not only for the murder of Frances Coles, but also for the other murders.

However, the case against him soon collapsed and Sadler was cleared of any involvement and released.

THE END OF THE MURDERS

With the murder of Frances Coles, "by person or persons unknown" the Whitechapel Murders came to an end and, shortly afterwards, the file itself was closed.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

SOURCE

https://www.jack-the-ripper.org/jack-the-ripper-history.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_the_Ripper